9 Sep 2023

The Mortal Sin of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

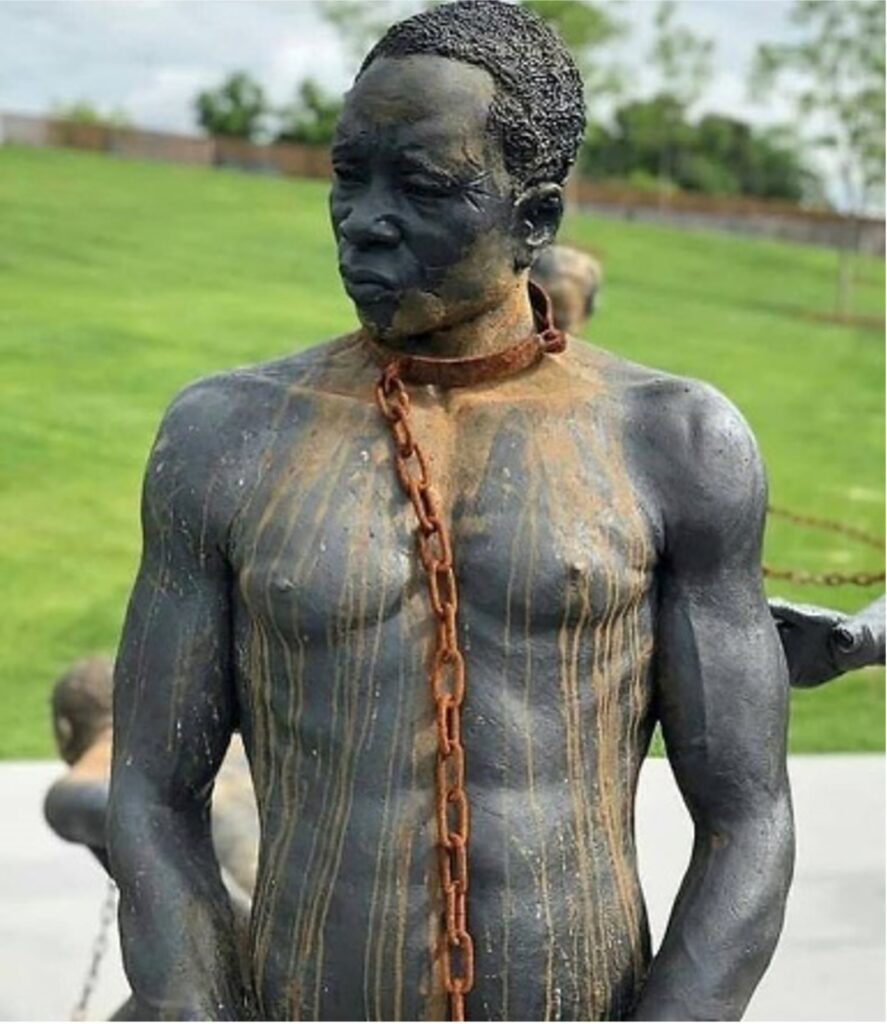

(Photo: Detail of a sculpture by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo dedicated to the memory of the victims of the transatlantic slave trade at the entrance of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama)

When I first went online for hagiography about St. Peter Claver—whom I confess I naively and ignorantly imagined to be a Black man—I learned that he was a white priest from aristocratic Spain serving in the early seventeenth-century slave port of Cartagena, Columbia.

Once known as the Apostle to the Negroes and now known as the patron saint of African missions and interracial justice, Peter Claver would rush to the slave ships with food and medicine. Over a period of forty-five years, kidnapped and enslaved African men, women, and children disembarked from as many as sixteen or seventeen ships a year in Cartagena. During thirty-four of those years, Peter Claver baptized countless enslaved thousands, whose African names were discarded by their slaveholders, to be forgotten. He called himself “the slave of the slaves forever,” and this phrase has found its way into the opening prayer of today’s Mass:

O God, who made Saint Peter Claver a slave of slaves

and strengthened him with wonderful charity and patience

as he came to their help,

grant, through his intercession,

that, seeking the things of Jesus Christ,

we may love our neighbor in deeds and in truth.

I think theologian Katie M. Grimes would have a problem with this prayer. In an article published by Cambridge University Press, Grimes has pointed out that Peter Claver was a privileged white priest who owned and physically disciplined his enslaved translators and whose catechesis was laced with white supremacist tropes. In her article, Grimes cites, “Through the interpreters, he told them that they had come to them to be the Father of all them and to make sure they were well received in the land of the whites where they had just now arrived. He would give them many other reasons and words of love and fervor in order to alleviate them of the fear that . . . the whites had brought them to their lands in order to kill them and make butter from their flesh.”

In contrast to this kind of white supremacist catechetical ideology, I think about two of the great-grandmothers of my Resurrectionist friend, Fr. Manuel Williams, who were daughters or granddaughters of emancipated former slaves. Despite the “undaughtering” of their enslaved parents, their lives bore testimony to steadfast Christian faith and to the Power of the Holy Spirit freely given and freely received in baptism. Such faith contradicts and condemns the forced enslavement, forced labor, and even forced baptism experienced by millions in the transatlantic slave trade as practiced in Cartagena and in chattel slavery as practiced in the United States.

Yes, I have a problem with white supremacist hagiography. And yes, I deeply admire the authentic witness of the faith-filled Christian descendants of those countless enslaved ancestors whose names, even though lost to memory, are cherished in our hearts and the heart of God.

Perhaps we can proclaim the first reading of today’s Mass from chapter 1 of the Letter to the Colossians in the memory of our unjustly enslaved ancestors.

Colossians 1:21-23

Brothers and sisters:

You once were alienated and hostile in mind because of evil deeds;

God has now reconciled you

in the fleshly Body of Christ through his death,

to present you holy, without blemish,

and irreproachable before him,

provided that you persevere in the faith,

firmly grounded, stable,

and not shifting from the hope of the Gospel that you heard. . . .

Scripture passage from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

10 September 2023 @ 1:02 am

Thank you Fr. Gregory for bringing the light of Truth in your preaching of St. Peter Claver and our sinfulness of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. May God have mercy on us.

Blessings on your continued preaching,

Brigid, OP

10 September 2023 @ 1:32 am

SO POWERFUL! Thank you for surfacing the white supremacist catechetical ideology — making ‘holy’ the sin of enslavement. I could not help but realize how often a similar catechetical ideology exists regarding aging in our later years. “Good” writers and speakers too often reflect such negative, false myths about aging and pass it off as spirituality.

10 September 2023 @ 2:06 am

Thank you, Lord have mercy on us, Christ hear our prayer. Kylie eleison.

10 September 2023 @ 4:33 am

And the whitewashing concerning the slave trade in the Americas continues to raise its ugly head via the attempts in certain states to introduce revisionist text books into our schools. We need to hear more such preaching . Thank you, Father Greg, and may God continue to bless your ministry.

10 September 2023 @ 7:25 am

Thank you for making me aware of Saint Peter Claver. I dug into a few more sources than Grimes and his is hardly the black and white (sorry) story painted here. Slavery was, and continues to be, anathema. But labeling every issue with color in it as “white supremacy” is dialectical and far from providing solutions. Lord, give us the grace to strive toward real virtue in our lives. Amen

10 September 2023 @ 8:57 am

Thank you for your light on Fr. Peter Claver.

Have mercy on us, dear Lord.

11 September 2023 @ 4:04 pm

Thank you Fr. Heille, powerful and insightful preaching.